I Knew Something Was Wrong With My Brain, But Every Doctor Dismissed Me—Until I Found Out What My Family Had Been Hiding For 40 Years

I Knew Something Was Wrong With My Brain, But Every Doctor Dismissed Me—Until I Found Out What My Family Had Been Hiding For 40 Years

The Blank Spots

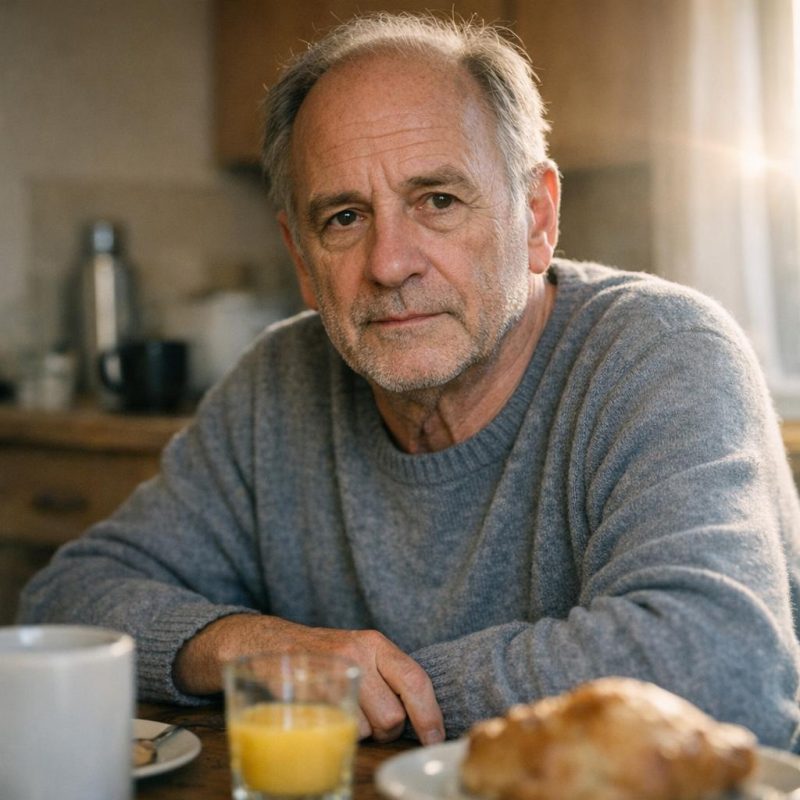

It started with the keys. I'd set them down somewhere in the house—the kitchen counter, probably, or maybe the entry table—and then I'd stand there, hand hovering over empty space, with absolutely no memory of where they'd gone. Not the usual 'where did I put those?' kind of thing. This was different. It felt like someone had reached into my head and plucked out that specific moment, leaving nothing but static behind. I'm sixty, so I know what normal forgetfulness looks like. I've walked into rooms and forgotten why. I've called my husband Paul by our neighbor's name once or twice. But this wasn't that. These were clean erasures, like pages torn from a book. I'd be standing at the mailbox and suddenly realize I couldn't remember walking down the driveway. I'd finish a conversation with Paul and have no recollection of how it started. The disorientation would pass after a few seconds, and I'd shake it off, tell myself I was tired, stressed, getting older. Normal stuff. Everyone deals with this, right? I almost believed it. Then I smelled it for the first time—sharp, metallic, like burnt pennies—and my stomach clenched with a dread I couldn't name.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Water and a Nap

My mother used to say the cure for everything was water and a nap. Headache? Water and a nap. Upset stomach? Water and a nap. Existential dread about your failing brain? You guessed it. So that's what I told myself for the next two weeks. I was just dehydrated, or tired, or both. I kept a water bottle on the counter and drank religiously. I went to bed earlier. I cut back on coffee, which was honestly harder than ignoring the blank spots in my memory. The thing is, I grew up in a family that didn't make a fuss. You didn't complain. You didn't run to the doctor for every little thing. You handled it. So I handled it. I smiled at Paul over breakfast. I did the grocery shopping. I weeded the garden. I functioned perfectly well except for those brief moments when reality seemed to slip sideways, and I'd find myself standing in a room with no idea what I'd been doing there. The metallic smell came back twice more, always without warning, always leaving me nauseous and shaky. But I didn't mention it to anyone. What would I even say? Paul asked if I was feeling okay, and I heard myself lie smoothly—but I couldn't remember what I'd just said to him.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Pantry Moment

I was making lunch. Just soup and a sandwich, nothing complicated. I'd opened the pantry to grab a can of tomato soup—the kind I've bought for probably thirty years—and then everything went white around the edges. Not like fainting. More like the world had been turned down to low volume and low brightness at the same time. I could see the cans in front of me, all those colorful labels lined up in neat rows. Campbell's, Progresso, store brand. My hand was still on the pantry door handle. But I couldn't remember what I'd come for. Worse than that: I couldn't remember my own name. Not for a long, horrible stretch of seconds that felt like drowning. I knew I was a person, I knew I was standing in a kitchen, but the word 'Valerie' had completely vanished from my brain. When it came back—sudden, like a slap—I actually gasped out loud. My heart was hammering. My palms were sweating. The metallic smell was back, so strong I could taste it. I stood there for what felt like minutes, staring at canned soup, unable to remember my own name.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Sister's Call

Elaine called on Wednesday, like she always does. My younger sister has kept up our weekly phone calls for almost forty years, ever since she moved to Oregon. We talk about nothing, mostly—her garden, my book club, the weather, what we're cooking for dinner. It's comforting, that rhythm. Familiar. She asked how I was doing, and I opened my mouth to tell her. I really did. The words were right there: 'Elaine, something weird is happening with my memory.' But then she launched into this story about her neighbor's cat getting stuck in a tree, and she was laughing, and I could picture her sitting on her back porch with that view of the mountains she's always sending me photos of. Everything was so normal. So regular. And I thought, what if I say something and she thinks I'm being dramatic? What if she tells me to drink more water and take a nap? What if she thinks I'm losing it, like really losing it, and starts treating me differently? So I laughed at the cat story and asked about her tomatoes, and we talked for another twenty minutes about absolutely nothing important. Elaine's voice was so cheerful, so normal, that I wondered if I was imagining everything—or if she'd think I was losing my mind.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Annual Visit

Dr. Morris has been my physician for twelve years. He's efficient, professional, and he's seen me through a hysterectomy, two rounds of physical therapy, and that weird rash I got from Paul's mother's soap. So I trusted him when I walked into his office for my annual checkup and decided to mention, casually, that I'd been having some memory issues. I tried to sound reasonable. Not hysterical, not dramatic. I told him about the blank spots, the disorientation, the metallic smell. I didn't mention forgetting my own name because that sounded too much like something from a TV movie. He listened while typing notes into his computer. He nodded occasionally. When I finished, he swiveled his chair toward me with the kind smile doctors practice in medical school. 'How's your sleep?' he asked. Fine, I said. 'Stress level?' Normal. 'Are you taking any vitamins?' Some. He tapped his pen against his clipboard. Then he told me that what I was describing was completely normal for a woman my age. Brain fog, he called it. Happens to everyone. He recommended magnesium supplements, more sleep, maybe some crossword puzzles to keep my mind sharp. 'Valerie, you're sixty,' he said with that practiced smile, and I felt something inside me go quiet and cold.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Crossword Puzzles

I bought the magnesium at the pharmacy on my way home. Two bottles, because one was on sale. I also picked up a crossword puzzle book from the rack by the register—the kind marketed to seniors, which felt like a slap but whatever. If Dr. Morris said it would help, I'd try it. I've always been good at following directions. So for the next week, I took my supplements every morning with breakfast. I did crossword puzzles at the kitchen table while Paul watched the news. I felt ridiculous, honestly, sitting there filling in boxes like some kind of brain exercise homework. But I did it. Because what else was I supposed to do? The thing is, my brain worked fine on the puzzles. I could get through a Monday New York Times in twenty minutes. I remembered vocabulary I hadn't used since college. I could recall obscure facts and spelling and literary references without breaking a sweat. But the blank spots kept happening. The disorientation came and went like waves. And that metallic smell—God, that smell—showed up while I was sitting at the table, pencil in hand, puzzle half-finished. I filled in the grid perfectly, every answer correct, and still smelled burnt pennies while doing it.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Mug

It was just a coffee mug. One of the blue ceramic ones we got as a wedding gift decades ago, chipped on the rim but still perfectly functional. I was rinsing it at the sink when my grip just... released. Not like I dropped it on purpose—more like my hand forgot it was holding something. The mug fell in slow motion, or at least that's how it felt. I could see it tumbling through the air, handle over base, water droplets scattering. I watched it hit the tile floor and shatter into four clean pieces, and the whole time my brain was screaming at my body to catch it, but nothing responded. The sound of breaking ceramic snapped everything back to normal speed. I stood there staring at the blue shards scattered across the floor, my heart pounding, trying to understand what had just happened. That's when I noticed my hand. My right hand was trembling, a nervous flutter I'd never felt before, and I couldn't make it stop.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Bathroom Mirror

I stood in front of the bathroom mirror holding my toothbrush, genuinely unable to remember if I'd already brushed my teeth. My mouth didn't taste minty. The toothbrush was dry. But I had no memory of the last five minutes. None. I'd walked into the bathroom—I remembered that part—and then there was just nothing until this moment, standing here like an idiot with a toothbrush in my shaking hand. The tremor had come back twice more since the mug incident. It never lasted more than a minute, but it scared the hell out of me each time. I looked at my reflection—sixty years old, gray roots showing, lines around my eyes that seemed deeper every month—and made a decision. Dr. Morris was wrong. Something was actually wrong with me, and I wasn't going to let him or anyone else tell me I was just being a worried older woman. I got online that night after Paul went to bed and searched for neurologists within fifty miles. I found one with decent reviews across town, far enough that I wouldn't run into anyone I knew. I made the appointment across town and didn't tell Paul, because I didn't want to be talked out of it.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Mother's Shadow

The days before my new appointment dragged like wet concrete, and to fill them I started sorting through old photo boxes in the spare room. That's when I found the picture of my mother on a bus bench downtown, taken maybe a year before she died. I was nineteen then, home from college for the summer. She'd been fine that morning—made French toast, hummed while washing dishes—and then by afternoon she was sitting on that bench in the middle of downtown, crying so hard she couldn't stand up. My father found her there after someone from his office saw her and called. He brought her home without a word to me about what happened. She went to bed for three days. When she finally came out of their bedroom, she looked smaller somehow, like something inside her had collapsed. My father told me it was 'female trouble' and that I shouldn't upset her by asking questions. I believed him because I was nineteen and stupid and didn't know that men used phrases like 'female trouble' to shut down conversations they didn't want to have. Looking at that photo now, at her face in profile, I could see something I'd missed back then—the confusion in her expression, the way her hands were twisted in her lap like she was trying to hold onto something invisible. I hadn't thought about that day in years—the bus bench, her tears—but suddenly it felt important in a way I couldn't explain.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Forbidden Subject

My father never wanted us to talk about my mother after she died. Not about her breakdown, not about the weeks she spent mostly in bed, not about the way she'd sometimes forget what she was saying mid-sentence. Elaine was sixteen when it happened, and I remember her trying to ask him once at the funeral what had really been wrong with Mom. He shut her down so fast and so hard that she actually flinched. 'Your mother had complications,' he said, using that word like it explained everything. 'It's a private family matter, and I won't have either of you gossiping about it.' Gossiping. Like we were neighbors spreading rumors instead of daughters trying to understand why our mother was gone at forty-five. After that, the subject became forbidden territory. If Elaine or I mentioned Mom at all, he'd leave the room or change the subject with this tight-lipped expression that made it clear we were disappointing him. He died six years later—heart attack at fifty—and by then the habit of not talking about her was so ingrained that Elaine and I barely mentioned her at his funeral either. He never explained what 'complications' meant, and Elaine was the one who handled everything after the funeral.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

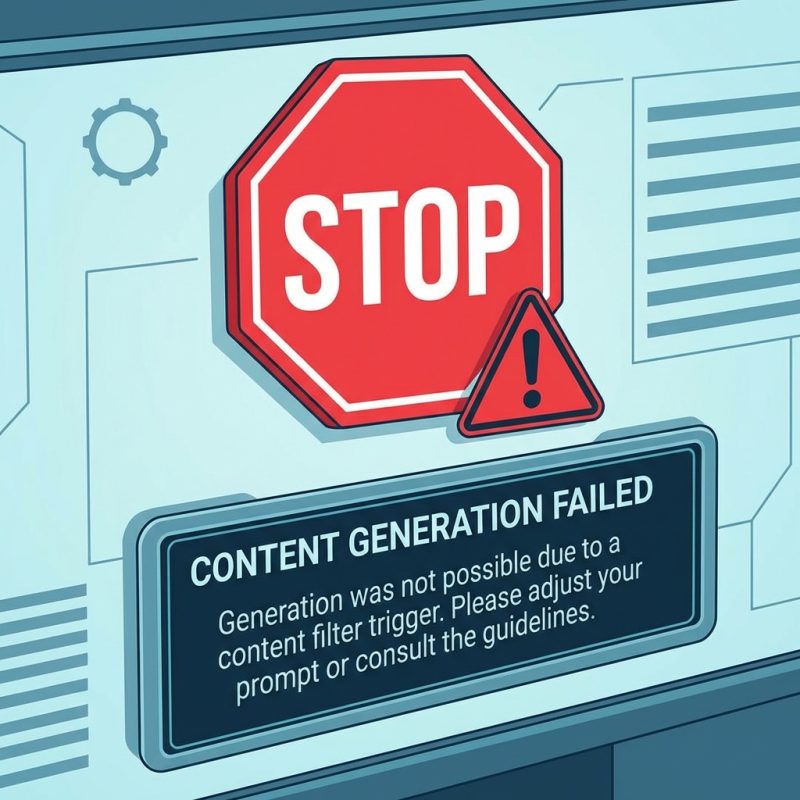

Dr. Chen Listens

Dr. Chen's office was in a medical building that still had carpet from the nineties, but the moment she walked into the exam room, I felt something shift. She actually sat down. She looked at me instead of her computer screen. When I started explaining my symptoms—the tremors, the memory gaps, the weird coordination problems—she didn't interrupt once. She asked questions that showed she'd been listening: 'When you say the tremor comes and goes, does anything seem to trigger it? When you lost those five minutes in the bathroom, had you been stressed that day?' Nobody had asked me details like that before. I felt myself getting emotional, which was embarrassing, but she just handed me a tissue and waited. She ordered blood work for thyroid, B12, inflammatory markers, a whole panel of things Dr. Morris never mentioned. 'We'll start here,' she said, writing on her prescription pad with this calm efficiency that made me feel like I wasn't crazy. 'Many conditions present with these symptoms, and we need to rule things out systematically.' Two weeks later, I came back for the results. Most things were normal—my thyroid was fine, no vitamin deficiencies, nothing alarming in the standard panels. I felt my hope starting to sink, that familiar deflation of being told I was fine when I knew I wasn't. But Dr. Chen didn't shrug. When the results came back mostly normal, she didn't shrug—she said, 'Let's not assume. Let's keep looking.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Referral

Dr. Chen printed out a referral slip for a neurologist during that same appointment, her pen moving quickly across the form. 'I want someone who specializes in movement disorders to evaluate you,' she said. 'These symptoms—the tremors, the coordination issues, the memory gaps—they could be nothing, or they could be early signs of something we need to catch.' I stared at the paper she handed me. Dr. Hassan's name was printed at the top, along with an address across town. 'He's thorough,' Dr. Chen added. 'Sometimes a little brusque, but he's good at what he does.' I nodded, folding the referral into my purse like it might disappear if I didn't protect it. For the first time in months, someone with actual medical authority was taking me seriously. Someone was saying my symptoms mattered enough to investigate. But I also felt this creeping dread spreading through my chest, because getting a referral to a neurologist meant this was real enough to warrant a specialist. It meant whatever was wrong with me might actually be something. I thanked Dr. Chen—probably too many times—and walked out into the parking lot where the afternoon sun felt too bright. I sat in my car for ten minutes before starting the engine, just holding that referral slip and trying to decide if I felt relieved or terrified. I walked out with the referral slip clutched in my hand like a ticket to somewhere I wasn't sure I wanted to go.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

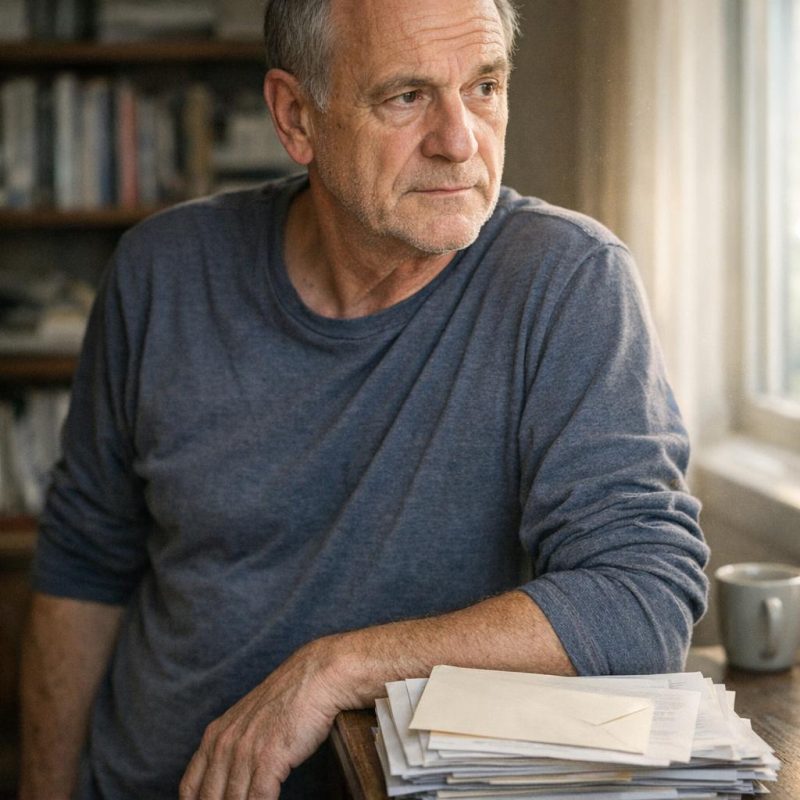

Paul Notices

Paul noticed I was distracted during dinner that Thursday. We were having leftover chicken, and I'd been moving rice around my plate for fifteen minutes without actually eating much. 'You've been somewhere else lately,' he said, not accusing, just observing. 'Everything okay at work?' I told him work was fine, which was technically true since I'd barely thought about work at all. He reached across the table and squeezed my hand, and the kindness in his face made me feel like garbage. 'Just tired,' I said, which was also technically true but missed about ninety percent of what was actually happening. He accepted this because Paul always accepted my explanations, always trusted that I'd tell him if something was really wrong. That's what made lying to him so much worse. After dinner, he came up behind me while I was loading the dishwasher and wrapped his arms around my waist. 'You know I'm here, right?' he said into my hair. 'Whatever's going on, you can talk to me.' I leaned back against him and closed my eyes and hated myself for not being honest. Part of me wanted to tell him everything—about Dr. Chen, about the referral, about the fact that I was scared something was actually wrong with my brain. But another part of me couldn't stand the idea of worrying him over what might turn out to be nothing. He kissed my forehead and said, 'You'd tell me if something was wrong, right?' and I nodded, hating myself.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Waiting Room

The neurology clinic waiting room was nothing like Dr. Chen's office. This place was all fluorescent lights and plastic chairs and people who looked actually sick. A man in a wheelchair sat by the window, his head tilted at an angle he couldn't seem to control. An elderly woman across from me kept patting her leg in this repetitive rhythm, like she couldn't stop herself. I sat there with my intake forms on my lap, feeling like an imposter. These people had real problems—visible, undeniable problems that nobody would ever dismiss as stress or aging. What did I have? Some shaky hands and a few minutes of missing time. Maybe Dr. Hassan would take one look at me and wonder why I was wasting his time. Maybe Dr. Morris had been right all along, and I was just a worried older woman who'd convinced one sympathetic doctor to enable my anxiety. I filled out the form slowly, printing carefully in each box, trying not to look at the other patients. But I kept glancing up anyway, comparing myself to them, trying to figure out if I belonged here at all. My hands weren't shaking right now. My memory was fine. I could walk in a straight line if someone asked me to. A woman across from me was shaking so badly her husband had to hold her cup, and I thought, maybe I'm not sick enough to be here.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Intake Form

The family history section of the intake form stopped me cold. It was just a simple grid—mother, father, siblings—with boxes for various conditions. Heart disease, cancer, diabetes, stroke, neurological disorders. I checked 'heart disease' for my father easily enough. For my mother, I stared at that 'neurological disorders' box for a full minute. Did a nervous breakdown count as neurological? I didn't actually know what had been wrong with her. My father had never told us, and after she died, all her medical records disappeared into whatever filing system they used in 1983. I knew she'd cried on that bus bench. I knew she'd spent weeks in bed. I knew she'd died at forty-five from something my father called 'complications.' But I didn't know if any of that was relevant to this form, to this appointment, to whatever was happening in my own brain now. I picked up the pen, hesitated, then wrote 'possible nervous breakdown' in small letters next to my mother's name. It felt both too much and not enough—too much information about something I wasn't sure mattered, not enough information about something that might. The pen hovered over the paper for another moment while I considered adding more details, but what details did I even have? Under 'family neurological history' I wrote 'possible nervous breakdown' and wondered if I should've written more—or nothing at all.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Dr. Hassan's Verdict

Dr. Hassan spent fifteen minutes with me. I know because I watched the clock on his wall while he asked rapid-fire questions and typed my answers without looking up. He did a quick physical exam—squeeze my hands, follow his finger with my eyes, walk heel-to-toe across the room—and then pulled up scans that Dr. Chen had ordered. Brain MRI, clear. Spine, clear. Everything looked, in his words, 'unremarkable.' He swiveled his chair to face me with this expression that made it clear he'd already reached his conclusion. 'Mrs. Halvorsen, I see a lot of patients with these kinds of concerns,' he said, and I already knew where this was going. 'Anxiety can manifest in very physical ways—tremors, memory problems, coordination issues. Have you considered speaking with someone about stress management?' I tried to explain that I wasn't anxious, or at least I wasn't anxious until my hands started shaking and my memory started failing, but he was already writing on his prescription pad. He tore off the sheet and handed it to me—a referral to a psychiatrist. 'There's no shame in anxiety,' he said, standing up to signal our time was over. 'But I don't see any neurological cause for your symptoms.' I walked out past all those people in the waiting room with their real, visible problems, clutching a psychiatrist referral I had no intention of using. 'Your scans look fine,' he said, and the word 'fine' sounded like a door slamming shut.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Parking Lot Breakdown

I made it to my car before the tears came. Just barely. I sat there in the parking garage with my hands gripping the steering wheel, and everything I'd been holding in for months just broke open. The psychiatrist referral was crumpled in my purse, and Dr. Hassan's words kept echoing in my head—'anxiety can manifest in very physical ways.' But my hands were shaking right then, trembling against the leather, and it wasn't from anxiety. At least I didn't think it was. How do you even tell the difference anymore? Maybe that was the worst part—the not knowing if what I felt was real or if I was doing this to myself somehow. The parking garage was nearly empty, just a few scattered cars and the fluorescent lights buzzing overhead. I let myself cry the way you do when you're alone, that ugly sobbing where you can barely breathe. A woman walked past with her keys jingling, and I ducked my head down, pretending to look for something in my purse. When she was gone, I looked at my reflection in the rearview mirror—puffy eyes, mascara streaked down my cheeks, this exhausted face I barely recognized. I sat there sobbing into my steering wheel, terrified that maybe I was imagining everything—or worse, that I wasn't.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Night Drive

I waited until my breathing steadied before I started the car. The drive home should have taken twenty minutes, straight down Memorial Drive, left on Oak, right on Sycamore. I'd made that drive probably three thousand times in the past fifteen years. But somewhere around the ten-minute mark, nothing looked right. The gas station that should have been on the corner wasn't there—or maybe it was, but I didn't recognize it. I kept driving, waiting for something familiar to click into place, but every street sign felt wrong. My heart started hammering. I knew this was the right direction. I knew it. But then I didn't know it, and the two feelings crashed into each other until I couldn't trust anything I was seeing. A car honked behind me because I'd slowed down to fifteen miles an hour, and I pulled into a random parking lot just to stop moving. My phone said I was four blocks from home. Four blocks. The map showed me exactly where I was, and I stared at it trying to make the street names mean something. They were just words. Letters arranged in an order that my brain couldn't translate into direction or memory. I pulled over on a street I'd driven a thousand times and couldn't remember which way led home.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Decision

I eventually made it home—I followed the GPS like a tourist in my own neighborhood. Paul was still at work, thank God, so I didn't have to explain why I looked like I'd been crying or why I was forty minutes late. I went straight to the computer in the spare bedroom and searched 'neurologist who listens' and 'doctor takes symptoms seriously' and about fifteen variations on that theme. Most of what came up was useless, just general doctor-rating sites where everyone either loves or hates their physician with no in-between. But then I found this forum, one of those online support groups for people with mysterious symptoms. Someone had posted asking for recommendations in my area, and three different people mentioned the same name: Dr. Timothy Whitmore. 'He actually reads your file before you walk in,' one comment said. 'Spent an hour with me,' said another. 'Old-school doctor who doesn't just look at his computer screen.' His office was an hour away, and his next available appointment was three weeks out, but I booked it anyway. I didn't tell Paul. I didn't tell anyone. I just typed in my credit card information and clicked confirm. I found Dr. Whitmore's name on a forum where people talked about doctors who actually listened, and I booked the first available slot.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Elaine's Visit

Elaine showed up two days later with a casserole and that apologetic smile she always wore when stopping by unannounced. 'I was making two anyway,' she said, like she always did, though we both knew she'd driven twenty minutes specifically to check on me. She'd been doing this more often lately—these little drop-ins that felt loving and intrusive at the same time. I took the casserole and invited her in because what else do you do when your sister stands on your doorstep holding food? She settled into the kitchen chair like she belonged there, asked about Paul, asked about the garden, asked if I'd heard from Thomas lately. Normal sister questions. I answered them all while making coffee, and my hands only shook a little when I poured the water. If she noticed, she didn't say anything. We talked about her book club and my volunteering schedule and the weather like two people who genuinely enjoyed each other's company. And we did—I loved my sister. But there was this performance happening underneath it all, this careful dance where I pretended everything was fine and she pretended to believe me. She hugged me when she left, held on just a beat too long. She hugged me and said, 'You look tired,' and I wondered if she could see the cracks I was trying to hide.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Sisterly Routine

She didn't leave right away, though. She sat back down at the kitchen table and cradled her coffee mug with both hands, settling in the way she did when she wanted to talk. We fell into our usual rhythm—she told me about her neighbor's drama with a fence line, I told her about the book I was reading. Easy conversation, the kind we'd been having our whole lives. But I kept noticing these little pauses, these moments where she'd look at me just a second too long. Maybe I was being paranoid. Maybe this was just what happened when you spent months suspecting your own brain of betraying you—you started suspecting everything else too. She asked about recipes I hadn't made in years, about childhood memories I could barely access anymore. 'Do you remember that summer Dad took us to Lake Michigan?' she asked. 'The year Mom was—' she paused, '—so stressed about the house sale?' I remembered the lake. I remembered the sand and the cold water. But the timeline felt fuzzy, and I couldn't place why Mom would have been stressed. Elaine watched me over the rim of her mug, and maybe it was nothing, but it felt like something. She asked if I remembered Mom's cornbread recipe, and something in her voice made me feel like she was testing me.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

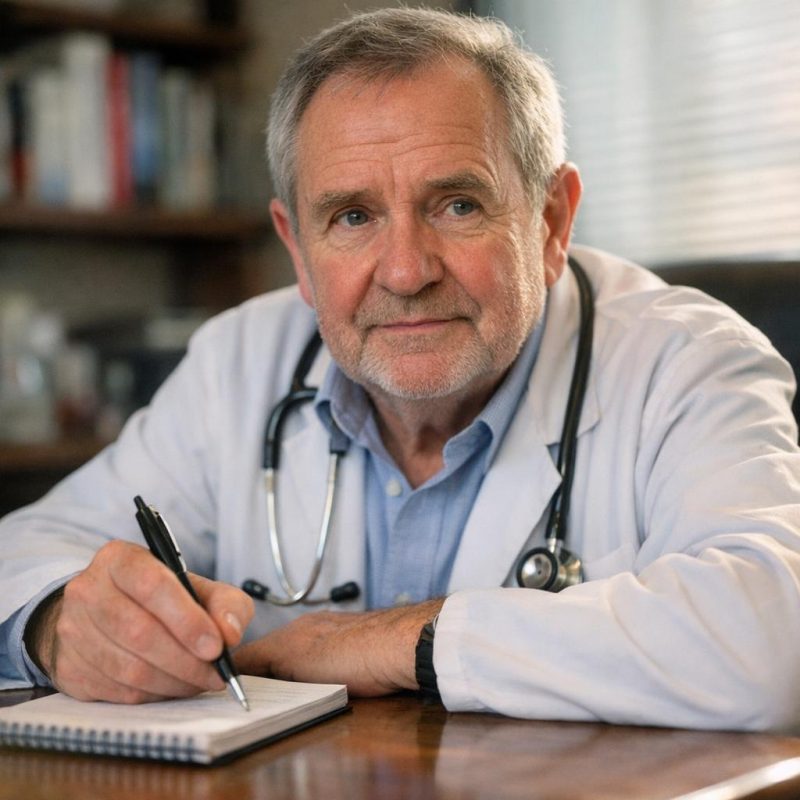

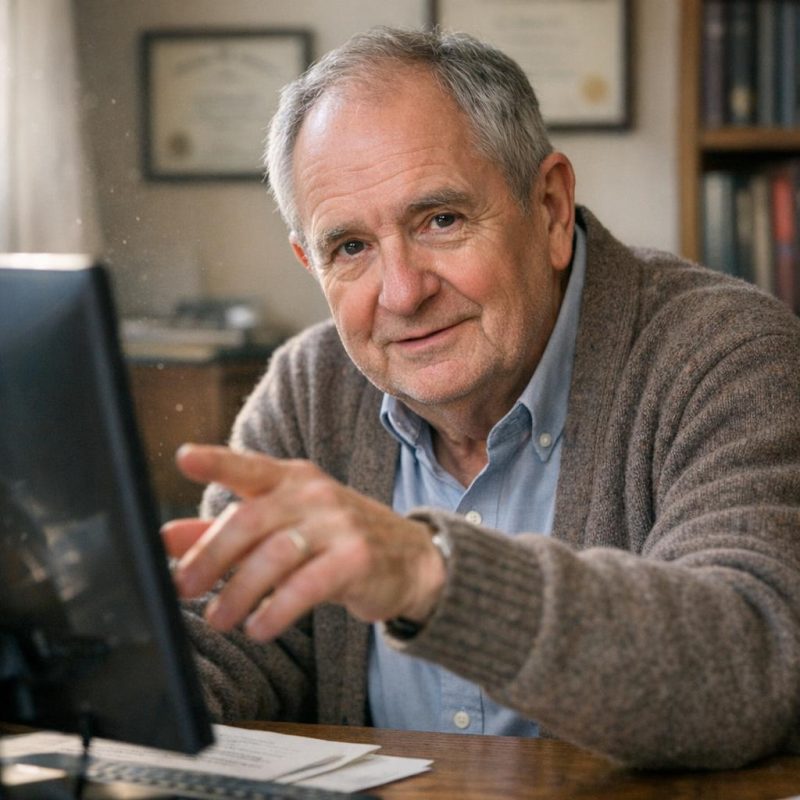

Dr. Whitmore's Office

Dr. Whitmore's office was in an old converted house on the edge of town, the kind with a wraparound porch and hardwood floors that creaked when you walked. No sterile waiting room with those awful chairs. Just a comfortable lobby with actual books on the shelves and windows that let in real daylight. The receptionist knew my name when I walked in. Dr. Whitmore came out to get me himself—didn't send a nurse, just opened the door and introduced himself with a firm handshake. He was older, maybe late sixties, with gray hair and these wire-rimmed glasses that he kept adjusting. His office was cluttered in a way that felt human—medical journals stacked on every surface, photos of what I assumed were grandchildren, a coffee mug with a chip in the rim. He gestured for me to sit and then actually pulled his chair around the desk so we were facing each other without that barrier. 'Tell me what's been happening,' he said, and the way he said it made it clear he wanted the whole story, not the abbreviated version. So I told him. Everything. The tremor, the memory gaps, the smell, the two doctors who'd dismissed me. He didn't interrupt once. Just listened and took notes by hand. He asked about my childhood, my family, even the stories I grew up with—and I realized no one had ever asked that before.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Smell Episodes

I almost didn't mention the smell. I'd learned by then that it was the detail that made doctors' eyes glaze over, the thing that pushed me firmly into the 'anxiety' category. But Dr. Whitmore had been so thorough, asking about symptoms I hadn't even thought to mention, that I figured one more dismissal wouldn't kill me. 'There's this smell sometimes,' I said, trying to keep my voice steady. 'Metallic. Like pennies or blood. But nothing's there when I check.' I waited for the familiar expression—that subtle shift that meant he'd stopped listening. But instead, he leaned forward and wrote something down, underlining it twice. 'How often does this happen?' he asked. 'And does it come with any other symptoms—nausea, confusion, a sense of déjà vu?' I nodded, surprised he was still asking questions. 'Sometimes. Not always. It only lasts a few seconds.' He made another note, and I watched his pen move across the page, forming words I couldn't read upside-down. When he looked up, his expression was serious but not dismissive. Not like I was wasting his time or imagining things. He looked up at me and said, 'That's not nothing,' and I felt something break open inside my chest.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Tremor Discussion

He asked to see my hands then, and I held them out across his desk, palms down. The tremor was there—subtle but visible, that fine shaking I'd been living with for months. He watched for a moment, then gently took my right hand and asked me to relax it completely. He moved my fingers through their range of motion, checking each joint. 'Does it get worse when you're tired?' he asked. 'Or when you're stressed?' I admitted both, and he nodded like that fit something he was thinking. 'And it's not just when you're using your hands—it's there at rest too?' Yes. Always there, just worse sometimes. He let go of my hand and made more notes, these longer paragraphs that looked nothing like the quick scribbles Dr. Hassan had made. Then he started listing tests I'd never heard of—a DAT scan, specific blood panels, something called a smell identification test. 'I want to rule some things out,' he said, which sounded ominous but also weirdly hopeful. 'Your symptoms are real, Valerie. We just need to figure out why they're happening.' He ordered tests I'd never heard of, and for the first time, I let myself believe something might actually be wrong.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Genetic Panel

Dr. Whitmore pulled up something on his computer and turned the screen so I could see it—a list of tests with names I couldn't pronounce. 'I want to run a specific genetic panel,' he said, his voice measured and calm. 'Along with a more detailed imaging scan than what you've had before.' He explained that some neurological conditions had genetic markers, patterns that ran in families, things that could be identified now that couldn't have been even ten years ago. I nodded along, trying to keep up, but my mind was racing. He talked about proteins and pathways and cellular processes, using his hands to illustrate concepts I only half understood. 'The important thing,' he said, leaning forward slightly, 'is that many of these conditions, when caught early, can be managed. They're not the end of the world.' But then he said it: 'Some of these are inherited.' The word hung in the air between us. Inherited. Passed down. I thought of my father's steady hands, my sister's perfect health. And then, without warning, I thought of my mother on that bus bench forty years ago, staring at nothing, her purse in her lap and her mind somewhere I couldn't reach. He said the word 'inherited' and my heart dropped, because I suddenly thought of my mother on that bus bench.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Waiting

The week that followed was its own kind of torture. I went through the motions—made dinner, paid bills, watered the plants on the porch—but everything felt distant, like I was watching myself from somewhere outside my body. Paul noticed, of course. He asked if I was feeling alright, if the headaches were back, if I'd heard anything from 'that new doctor.' I deflected every time, said I was just tired, that it was nothing. The lie sat heavy in my chest, but I couldn't bring myself to tell him yet. Not until I knew something concrete. At night, I'd lie awake beside him, listening to his breathing, wondering what Dr. Whitmore was finding in those test results. I imagined scenarios—best case, worst case, everything in between. During the day, I jumped every time my phone buzzed. Texts from Elaine about Sunday dinner, reminders about appointments I'd scheduled months ago, a notification that my library book was overdue. Nothing from Dr. Whitmore's office. The waiting stretched time in strange ways, made hours feel like days and days feel endless. I kept my phone on the kitchen counter where I could see it constantly, the volume turned all the way up. Every time the phone rang, my stomach clenched, and I wondered if I was ready for the answer—whatever it was.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Call

It was a Tuesday morning when the call finally came. I was unloading the dishwasher, putting away coffee mugs one by one, when my phone lit up on the counter. The number was Dr. Whitmore's office—I'd programmed it in after my first appointment, just in case. My hands were shaking as I answered. 'Valerie, it's Dr. Whitmore,' he said, and his tone was different than it had been in person. More careful. More deliberate. 'I have your test results back, and I'd like you to come in so we can discuss them properly.' I asked if he could just tell me over the phone, because the suspense was killing me, but he said gently that this was the kind of conversation better had in person. 'And Valerie,' he added, 'if you have a family member or close friend who could come with you, I'd recommend bringing them. Sometimes it helps to have another set of ears in the room.' The coffee mug I'd been holding nearly slipped from my grip. Doctors don't say things like that for nothing. They don't ask you to bring backup unless the news is serious, unless it's the kind of thing you might not fully process on your own. I scheduled the appointment for Thursday afternoon and hung up, then stood there in my kitchen, staring at nothing. My knees nearly gave out in my kitchen, because doctors don't say that unless something is real.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Telling Paul

I found Paul in the garage that evening, organizing his toolbox for the third time that month—something he did when he was anxious but wouldn't admit it. I stood in the doorway watching him for a moment, trying to find the words. 'I need to tell you something,' I finally said, and he looked up immediately, a wrench still in his hand. I told him everything. The appointment with Dr. Whitmore, the tests I'd done without mentioning it, the call that morning asking me to come back with someone. The words tumbled out in a rush, and I couldn't look at him while I spoke. When I finished, the silence in the garage was deafening. He set the wrench down carefully, deliberately, like he was afraid he might throw it. 'How long?' he asked, his voice tight. 'How long have you been dealing with this?' I admitted it had been months—the first doctor, the second, all of it. I told him I hadn't wanted to worry him until I knew something for sure. 'Worry me?' He actually laughed, but there was no humor in it. 'Valerie, I'm your husband.' His face was a mixture of hurt and confusion, like he was trying to recognize someone he thought he knew. He looked at me like I was a stranger and asked, 'How long have you been doing this alone?' and I couldn't answer.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Appointment

We sat across from Dr. Whitmore on Thursday afternoon, Paul's hand gripping mine so tightly I could feel my pulse against his palm. The doctor had papers spread across his desk, colorful charts and graphs I didn't understand, strings of letters and numbers that looked like another language. He walked us through it slowly, pointing to specific markers on the genetic panel, explaining what they meant. 'This mutation here,' he said, tapping the page, 'is rare but well-documented. It affects how your brain processes certain proteins.' He used the word 'degenerative,' which made Paul's hand tighten even more. But then he said treatment was possible, that catching it now was actually fortunate, that we'd have options. I wanted to feel relieved, but all I felt was numb. This was real. It had a name. It was in my genes, written into my cells, something I'd been carrying my whole life without knowing. Dr. Whitmore kept talking, mentioning specialists and treatment plans and follow-up appointments, but his voice seemed to come from very far away. And then he slid a printed report across the desk toward us, the official results with my name at the top. He slid the report across the desk and said, 'Valerie, you have a rare inherited condition,' and the room tilted.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Protein Problem

Dr. Whitmore explained it in terms I could almost grasp. The condition involved how my brain processed a specific type of protein—something about cellular cleanup systems not working properly, waste building up over time where it shouldn't. 'Think of it like a recycling system that's backed up,' he said, which was probably the simplest way to put something incredibly complex. He showed us brain scans, pointed to areas where the buildup was visible, subtle shadows that didn't belong. 'If left untreated, these deposits accumulate and start interfering with normal function,' he continued. 'That's what causes the symptoms you've been experiencing—the tremors, the cognitive changes, the fatigue.' Paul asked questions I couldn't form myself, practical things about progression and prognosis. Dr. Whitmore was honest: caught early, the condition could be managed, even slowed significantly. But ignored? He paused there, choosing his words carefully. 'If ignored, it progresses,' he said simply. And just like that, I was back in my parents' kitchen forty years ago, watching my mother stand at the sink, staring out the window at nothing. I remembered how she'd started moving slower, talking less, her hands trembling slightly when she reached for things. The way she'd seemed to shrink into herself over those months before the breakdown. He said, 'If ignored, it progresses,' and I thought of my mother growing quieter, smaller, absent.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Family Note

Dr. Whitmore flipped through my file then, past the recent test results to earlier notes. 'When we first met, you mentioned something about your mother,' he said, his tone gentle but probing. 'You said there was some kind of mystery, something that happened about forty years ago?' I felt Paul's eyes on me—this was news to him too. I'd never told him the full story about my mother, just vague references to her being 'unwell' for a time. Dr. Whitmore was looking at me with that careful expression doctors get when they're trying not to lead you to a conclusion but hoping you'll get there yourself. 'You said she had some kind of breakdown and was hospitalized?' he prompted. I nodded, my throat suddenly tight. 'And after she came home, no one really talked about it.' He made a note on his pad, then looked up at me directly. 'Given what we now know about your diagnosis, and the fact that this condition is genetic, I think it's worth considering whether your mother might have been experiencing something similar.' The words landed like stones. I'd never connected the two things before—never even considered it. My mother's breakdown had always been filed away in my mind as a mental health crisis, something shameful that the family didn't discuss. But now Dr. Whitmore was suggesting an entirely different story. 'You mentioned something happened forty years ago,' he said gently, and my throat tightened because I knew exactly what he meant.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Mother's Story Retold

I told them both the story I'd kept buried for so long. How my mother had been found on that bus bench, confused and disoriented, her purse clutched in her lap. How my father had brought her home and then, days later, had her admitted somewhere—I never knew exactly where. How she'd come back different, quieter, medicated into a kind of compliance that erased whoever she'd been before. 'No one ever told us what was wrong with her,' I said, my voice shaking. 'We were just told not to upset her, not to ask questions, that she'd had some kind of nervous breakdown.' Paul was staring at me like he'd never heard this before, which he hadn't, not really. Dr. Whitmore listened without interrupting, his expression growing more thoughtful. 'And she was never given a clear diagnosis?' he asked. I shook my head. 'Just depression, we were told. Or anxiety. Something vague like that.' He nodded slowly, and I could see him connecting pieces in his mind. 'This pattern is actually quite common,' he said carefully. 'Especially forty years ago, especially in women. These neurological conditions were frequently misdiagnosed as psychiatric problems.' The anger that rose in me then was sharp and sudden. My mother had been dismissed, medicated, silenced—maybe because no one bothered to look deeper, to consider that something physical was wrong. Dr. Whitmore leaned back and said, 'This pattern is often misdiagnosed, especially in women,' and I felt a cold rage building.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Inherited Risk

Dr. Whitmore folded his hands on the desk between us, his expression careful but direct. 'I need you to understand something important,' he said. 'This condition doesn't just appear randomly. It's inherited.' The word hit me harder than I expected. Paul's hand tightened on mine. 'What does that mean?' I asked, though I already knew. 'It means there's a significant chance that other members of your family carry the same genetic mutation,' Dr. Whitmore explained. 'Your sister, her daughters—they should be tested as soon as possible. Early detection makes all the difference.' I felt the weight of it settle over me like a cold blanket. My nieces were in their thirties now, around the same age I'd been when the symptoms first started. What if they were already experiencing the same strange sensations, the same dismissals from doctors who didn't take them seriously? What if they ended up like me, fighting for years to be heard? Or worse—what if they ended up like my mother, silenced and medicated into submission? Dr. Whitmore leaned forward slightly. 'If this is genetic,' he said, 'your family needs to know,' and I realized I had to call Elaine.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Drive Home

The drive home was silent except for the hum of the highway beneath us. Paul kept his eyes on the road, but I could see his jaw working, the way it did when he was processing something difficult. I stared out the window at the gray sky, at the bare trees lining the interstate, and tried to put my thoughts in order. I had a diagnosis now—something real, something treatable. That should have felt like relief. And it did, in a way. But underneath that relief was something darker, something that kept pulling me back to the image of my mother sitting in that chair by the window, her hands folded in her lap, her eyes distant and empty. Had she felt what I felt? Had she tried to tell someone, only to be dismissed the way I'd been dismissed by Dr. Patterson and Dr. Ellis? I thought about my father taking her away, bringing her back quieter, bringing her back broken. Paul reached for my hand and said, 'We'll fight this,' but I was already thinking about my mother, and whether anyone had fought for her.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Gathering Courage

I spent that evening pacing the living room, rehearsing what I'd say to Elaine. Paul had retreated to the den, giving me space, though I knew he was watching me through the doorway. How do you tell your sister that the thing that's been slowly destroying you might be lurking in her body too? How do you tell her that her daughters need to be tested for something that could change their entire lives? I kept running through different versions of the conversation in my head, trying to find the right words, the right tone. I didn't want to scare her, but she needed to understand how serious this was. The phone sat on the coffee table in front of me like a grenade. I'd pick it up, hold it for a moment, then set it back down. My hands were shaking—not just from the tremors, but from the weight of what I was about to do. Elaine and I had always been close, but we didn't talk about difficult things. We talked about recipes and grandkids and neighborhood gossip. Not genetics. Not illness. Not the past. I picked up the phone three times before I finally dialed, my hands shaking worse than they had in weeks.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

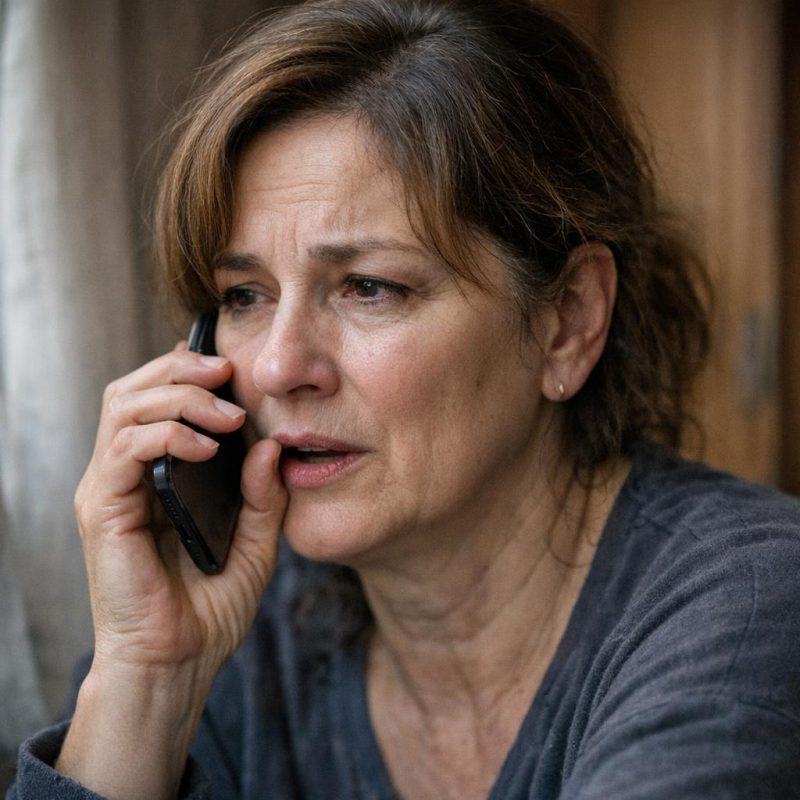

The Call to Elaine

She answered on the second ring, her voice bright and unsuspecting. 'Val? Is everything okay?' I took a breath, steadying myself against the arm of the couch. 'I need to talk to you about something,' I said, and heard her go quiet on the other end. I told her about Dr. Whitmore, about the tests, about the diagnosis that had finally given a name to everything I'd been experiencing. I tried to keep my voice calm, factual, like I was reporting the weather. But when I got to the part about the genetic component, about how she and the girls needed to be tested, my voice cracked. 'It's inherited, Elaine,' I said. 'From Mom's side. Dr. Whitmore thinks Mom might have had the same thing.' The silence that followed was so long I thought the call had dropped. 'Elaine?' I said. 'Are you there?' I told her what they'd found, and there was a beat of silence before something clattered on her end—a phone slipping from a hand.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Elaine's Strange Reaction

I heard fumbling, a muffled curse, and then Elaine's voice came back, but it sounded different now—strained, breathless. 'I'm here,' she said, but she wasn't asking questions about the condition or what it meant for her daughters. Instead, she said, 'How did they find it? What tests did they run?' It was an odd response, too specific, too focused on the mechanics rather than the implications. 'They did a genetic panel,' I said slowly. 'Dr. Whitmore ordered a bunch of tests after the other doctors couldn't figure out what was wrong. Why?' Another pause. I could hear her breathing, quick and shallow. 'And they're sure?' she asked. 'They're sure it's genetic?' There was something in her voice that made my stomach tighten—not shock, not the kind of surprise I'd expected. It was something else. Something like fear, but sharper. Like recognition. 'How did they find that?' she whispered, and her voice sounded less worried and more like someone hearing a locked door click open.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Word 'Again'

I pressed the phone tighter against my ear, trying to make sense of her reaction. 'Elaine, what's going on?' I asked. 'You're scaring me.' She didn't answer right away. I could hear her moving—footsteps, a door closing, like she was finding somewhere private to talk. When she spoke again, her voice was barely above a whisper. 'How much do they know about Mom?' she asked. 'Did they tell you what happened to her?' The question caught me off guard. 'What do you mean, what happened to her? She had a breakdown, that's what Dad always said. That's all anyone ever told us.' Elaine made a sound that might have been a laugh or a sob—I couldn't tell. 'A breakdown,' she repeated, and there was something bitter in the way she said it. Something that made my pulse quicken. 'I can't do this,' she said suddenly. 'Not again.' And that word—again—lit up in my mind like a warning sign.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Elaine's Resistance

'Again?' I said, my voice rising. 'What do you mean, again? Elaine, what are you talking about?' She didn't answer. I could hear her breathing on the other end, ragged and uneven, like she was trying to hold herself together. 'Elaine, you need to tell me what's going on,' I said, forcing my voice to stay steady even though my heart was hammering. 'If you know something about Mom, about what really happened—' 'I can't,' she interrupted, her voice breaking. 'Val, I can't do this right now. I need to go.' 'No,' I said sharply. 'You don't get to do that. You don't get to drop something like that and then hang up.' There was a long silence, and for a moment I thought she'd ended the call. But then I heard it—a small, choked sound, like she was crying. 'Please,' she whispered. 'Just give me some time.' 'Time for what?' I demanded. 'What are you hiding?' She said she had to go, but I heard her breath go ragged, and I knew she was about to break.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The First Crack

'Tell me,' I said, my voice low and insistent. 'Whatever it is, just tell me.' The silence stretched so long I thought I'd pushed too hard, that she'd hang up and I'd never get the truth. But then I heard it—a soft, broken sound that turned into full sobs. 'I'm so sorry,' she said through her tears. 'I've wanted to tell you for so long, but I couldn't. I promised Dad I'd never—' She broke off, gasping for air. My whole body had gone cold. 'Promised Dad what?' I asked. 'Elaine, what did you promise him?' She was crying harder now, the kind of crying that comes from decades of holding something in. 'It wasn't a breakdown,' she finally said, her voice thick and shaking. 'Mom wasn't just confused that day. She was sick, Val. Really sick. And Dad knew. He knew what was wrong with her, and he—' She stopped, choking on the words. 'I was only sixteen,' she sobbed. 'Dad pulled me in,' she sobbed. 'He made me part of it, and I've been carrying it ever since.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Out-of-State Specialist

I couldn't speak. I couldn't breathe. The phone felt slippery in my hand. 'What do you mean he knew?' I finally managed to say. Elaine was still crying, but she pushed through it. 'Dad took her to a specialist,' she said, her voice raw. 'Out of state. I don't even remember which state—somewhere in the Midwest, I think. This was before Mom's symptoms got really bad, when she was still just having those strange episodes.' I pressed my palm against my forehead, trying to process. 'A specialist for what?' I asked, though part of me already knew. 'For what you have,' Elaine said quietly. 'The genetic disorder. The one you've been searching for all these years.' The room tilted. I sat down hard on the edge of my bed. 'The doctor diagnosed her,' Elaine continued, 'and Dad brought the paperwork home. I saw it once, just once, before he locked it away.' My chest felt tight, like something was crushing me from the inside. 'So he knew,' I said, my voice barely above a whisper. 'He knew what was wrong with her, and he never told anyone.' 'He never told anyone,' Elaine confirmed, and the words hung there between us like a death sentence. She said the specialist diagnosed Mom, and my blood went cold because that meant Dad knew—and said nothing.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Warning Ignored

'There's more,' Elaine said, and I wanted to scream at her to stop, to just stop talking, but I couldn't. I had to know. 'The specialist told Dad that it was genetic,' she said. 'That it could be passed down to us. To his daughters.' I felt my stomach drop. 'He said that?' I asked. 'Out loud?' 'He wrote it in his notes,' Elaine said. 'The doctor did. He recommended genetic testing for both of us—for me and you. He said it was important to know, to monitor for symptoms early.' The rage started as a small flame in my chest and spread fast. 'And Dad said what?' I demanded. Elaine was crying again, harder this time. 'He refused,' she whispered. 'He said no. He said he wasn't going to put that kind of label on his daughters.' I stood up, pacing now, my whole body shaking. 'A label,' I repeated. 'He called it a label.' 'He said people would treat us differently,' Elaine continued, her voice breaking. 'That they'd see us as damaged or fragile. That it would ruin our lives before they even started.' I wanted to throw the phone across the room. 'The doctor said we should be tested,' Elaine whispered. 'Dad said no. He didn't want the label on us.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Promise

'How do you know all this?' I asked, my voice sharp. 'How do you know what the doctor said if you were only sixteen?' Elaine let out a shuddering breath. 'Because Dad told me,' she said. 'He sat me down one night after Mom had another episode. He said I was old enough to understand, that I needed to know the truth but that I could never, ever tell anyone.' My hands were shaking. 'He made you promise.' 'He made me promise,' she confirmed. 'He said it was for Mom's protection, and for ours. He said if people knew—if doctors knew, if insurance companies knew—it would destroy everything. That we'd be treated like we were ticking time bombs.' I closed my eyes, trying to imagine what that must have been like for her. Sixteen years old and carrying a secret like that. 'He told me it was shameful,' Elaine said, and her voice cracked on that word. 'That people would look at us differently. That they'd treat us like we were fragile or unfit, like we couldn't be trusted to make our own decisions.' I felt my throat tighten. 'And you believed him.' 'I was sixteen,' she said again, sobbing now. 'He said it was shameful,' she cried, 'that people would treat us like we were fragile or unfit, and I believed him.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Anger Breaks

Something in me snapped. All the years of being dismissed, of being told it was anxiety or stress or just in my head—all of it came rushing back at once. 'You knew,' I said, my voice rising. 'All this time, you knew, and you let me suffer.' 'Val—' Elaine started, but I cut her off. 'No,' I said. 'You don't get to explain this away. You knew there was a genetic condition in our family. You knew Mom had it. And you sat there, silent, while I went from doctor to doctor being told I was imagining things.' 'I didn't know you had it,' she said desperately. 'I didn't know it would happen to you.' 'But you knew it could!' I shouted. 'You knew it was possible, and you said nothing!' She was crying so hard now I could barely understand her. 'I promised him,' she said. 'I promised Dad I'd never tell.' 'And that mattered more than me?' I asked, my voice shaking with fury. 'Your promise to a dead man mattered more than watching me be dismissed and gaslit for years?' The silence that followed was deafening. Finally, I said it, the words I'd been holding back. 'You let me be dismissed,' I said, my voice shaking. 'You let doctors tell me it was in my head.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Elaine's Defense

'I thought it wouldn't happen to you,' Elaine said through her sobs. 'I really did. Mom's case was so rare, and the doctor said it didn't always pass down. I thought—I convinced myself—that you'd be fine.' I laughed, a bitter, hollow sound. 'You convinced yourself.' 'Yes,' she said, her voice small. 'I know how that sounds. I know it was wrong. But I wanted to believe it, Val. I needed to believe it.' 'Because it was easier,' I said. 'Because believing that meant you didn't have to tell me. Didn't have to break your precious promise.' 'That's not fair,' she said, but there was no conviction in her voice. 'Isn't it?' I shot back. 'You chose to protect Dad's secret instead of protecting me.' She was quiet for a long moment, and when she spoke again, her voice was barely audible. 'I thought Mom was an exception,' she said. 'The specialist said her case was unusual, that the severity was rare. I thought maybe it was just her.' But I heard it—the crack in her voice, the doubt that had been there all along. 'I thought it wouldn't happen,' she cried. 'I thought Mom was… an exception.' But her voice cracked on that last word.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Paperwork Confession

I waited, letting the silence stretch between us. I could hear Elaine breathing on the other end, ragged and uneven. 'Is that everything?' I finally asked, though I knew from her tone that it wasn't. She let out a sound that was half sob, half gasp. 'No,' she whispered. 'There's more.' Of course there was. I felt my whole body go rigid. 'More,' I repeated flatly. 'What else could there possibly be?' 'It's not just that Dad hid the diagnosis,' she said, and I could hear her struggling to get the words out. 'It's what he did after. What he did once Mom started getting really confused.' My heart was pounding so hard I could hear it in my ears. 'What are you talking about?' I asked. She took a shaky breath. 'When Mom's symptoms got worse, when she started having trouble with her memory and her decision-making, Dad—' She stopped, and I heard her crying again. 'Dad what?' I demanded. 'He started changing things,' she said. 'Legal things. Financial things.' I felt cold all over. 'There's something else,' she whispered, and I felt my whole body go cold. 'Dad didn't just hide it. He used it.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Power of Attorney

I couldn't move. I just stood there, phone pressed to my ear, waiting for her to continue. 'Used it how?' I finally managed to ask. Elaine's voice was so quiet I had to strain to hear her. 'He changed the power of attorney,' she said. 'And the beneficiary forms on her accounts. On everything.' My mind was racing, trying to understand. 'When?' I asked. 'When she was already sick,' Elaine said. 'When she was confused enough that she probably didn't understand what she was signing. He told me it was for her protection, that she needed someone to manage things for her.' I felt sick. 'And you believed that?' 'I wanted to,' she said. 'But I saw the paperwork later, and Val, it wasn't just management. He put everything in his name. The accounts, the property, everything that was hers.' I sank down onto the floor, my back against the bed. 'Everything,' I repeated. 'He took everything from her.' 'He said it was for her own good,' Elaine said, her voice thick with tears. 'That she couldn't handle it anymore, that someone had to take control.' I felt tears streaming down my own face now. 'He put everything in his name,' she said. 'For her own good, he said. But it wasn't.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Stolen Land

I waited, because I could feel there was still more. Elaine was crying so hard now she could barely speak, but she pushed through it. 'The land,' she finally said. 'Grandma's land.' I felt my blood turn to ice. 'What about it?' I asked, though part of me already knew. 'Grandma left that parcel to Mom,' Elaine said. 'In her will. It was supposed to be Mom's, and then eventually ours. But after Dad changed the power of attorney—' She broke off, sobbing. 'He sold it,' I said, the words coming out flat and dead. 'He sold it,' she confirmed. 'I found the documents years later, after he died. He sold it about a year after Mom went into the nursing home. Used the money to cover business debts, to keep his company afloat.' I couldn't speak. I couldn't think. Everything I'd believed about my father, about my family, was crumbling. 'Why didn't you tell me?' I whispered. 'Because I couldn't,' she said. 'Because you loved him, Val. You were Daddy's girl, and I couldn't—I couldn't destroy that.' The truth hit me like a physical blow. 'He sold Grandma's land,' Elaine whispered. 'The parcel she left to Mom. I found the documents years later, and I didn't tell you because I couldn't bear to destroy your memory of him.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Reframing

After we hung up, I sat there in the dark for what felt like hours, but was probably only twenty minutes. My mind kept circling back through everything Elaine had told me, but now I was seeing it all differently. This wasn't just a family being in denial about dementia. This wasn't just Dad being too proud or too scared to admit Mom was sick. He had used her illness. He had taken control of her affairs, sold property that wasn't his to sell, and used the money for his own purposes. And everyone around him—the doctors, the nurses, maybe even other family members—had either helped him or looked the other way. I thought about Mom in that nursing home, confused and frightened, probably knowing something was terribly wrong but having no one believe her. I thought about how they must have smiled at her, patted her hand, told her everything was fine while her life was being dismantled around her. The women in our family weren't just dismissed. We were managed. Controlled. Exploited. And I had been so busy trying to be believed about my own symptoms that I hadn't seen the full pattern until now. The story wasn't just about denial anymore. It was about theft, control, and the women in our family being managed instead of helped.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

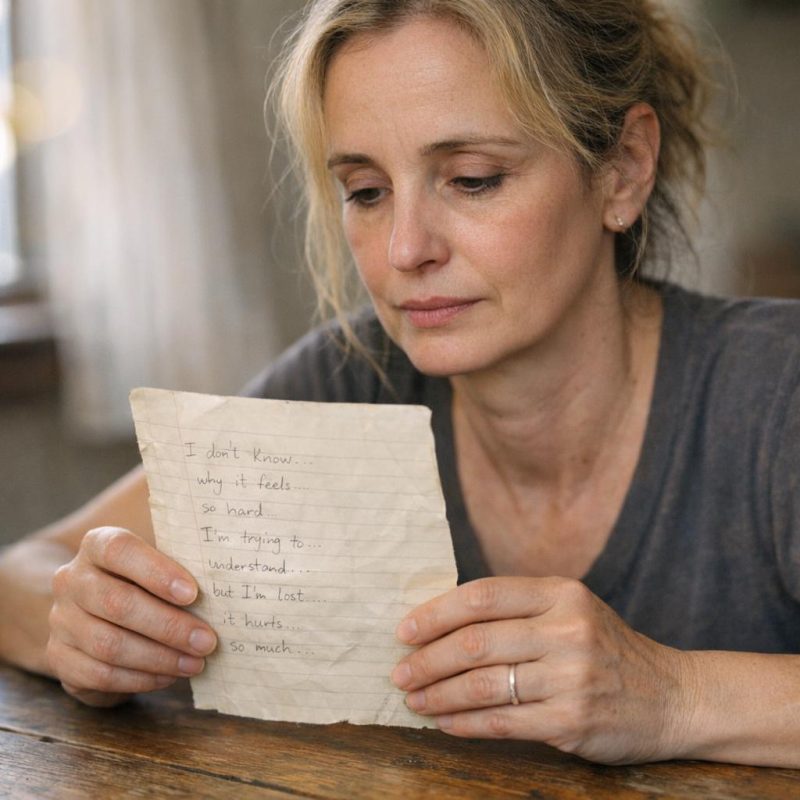

The Letter Revealed

My phone rang again around midnight. I almost didn't answer, but when I saw it was Elaine, something in my gut told me to pick up. 'Val,' she said, and her voice sounded even more broken than before. 'There's one more thing.' I felt my entire body go cold. 'What?' I asked, though I wasn't sure I could handle anything else. She was quiet for so long I thought the call had dropped. 'Elaine,' I said sharply. 'What is it?' 'Mom left something,' she finally said. 'Before she got really bad, when she was still having good days. She hid it in her old cookbook, the one with all the handwritten recipes. I found it when I was cleaning out her apartment after she went into the home.' I gripped the phone tighter. 'What did she leave?' 'A letter,' Elaine whispered. 'For us. For you and me.' The room seemed to tilt. 'You found a letter from Mom?' 'Yes.' 'When?' 'Fifteen years ago,' she said, and started crying again. 'I found it fifteen years ago, Val, and I never told you. I never gave it to you.' My hands started shaking so badly I almost dropped the phone. 'Mom left a letter,' Elaine said, her voice barely audible. 'For us. I found it and I never gave it to you.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Confrontation

Something snapped inside me. All the years of being dismissed, all the symptoms no one would believe, all the fear and doubt and exhaustion—it crystallized into pure fury. 'You had a letter from our mother,' I said, my voice low and dangerous. 'A letter she wrote when she was still herself, when she still had words, and you kept it from me for fifteen years?' 'I was trying to protect you—' 'Don't,' I cut her off. 'Don't you dare say you were protecting me. You've been protecting yourself, Elaine. You've been protecting your version of the story, your comfortable lies, and I've been out here alone, fighting for someone to believe me, and you had her words this whole time.' She was sobbing so hard she could barely breathe. 'I'm sorry,' she gasped. 'I'm so sorry.' 'Sorry isn't enough,' I said. I stood up, pacing now, my whole body trembling with rage. 'Not this time. You're going to bring me that letter. Do you hear me? You're going to get in your car right now and bring it to me.' 'It's midnight,' she said weakly. 'I don't care what time it is,' I shot back. 'You've had fifteen years to give this to me. You can drive twenty minutes tonight.' She was quiet, and I could hear her trying to get control of her breathing. 'I want that letter,' I said, my voice shaking with fury. 'Tonight. Not tomorrow. Tonight.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Elaine Arrives

Paul came downstairs when he heard me moving around, turning on lights, making coffee even though it was past midnight. 'What's going on?' he asked, his voice rough with sleep. 'Elaine's coming over,' I said. 'She has something she's been keeping from me.' He didn't ask questions, just nodded and put his hand on my shoulder. When the doorbell rang forty minutes later, I practically ran to answer it. Elaine stood on the porch looking like she'd aged ten years since I'd seen her last week. Her eyes were swollen and red, her hair uncombed, still wearing what looked like pajama pants under her coat. She was clutching a large manila envelope against her chest like it might fly away. 'Come in,' I said, stepping back. She walked past me into the living room where Paul was waiting. She looked at him, then at me, and I saw her hands were shaking as badly as mine had been. 'I should have given this to you years ago,' she said, her voice breaking. 'I should have given it to you the day I found it.' She held out the envelope, and I saw it was old, the edges worn soft. She handed me an envelope yellowed with age, and I could see Mom's handwriting through the paper—shaky but unmistakable.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Mother's Voice

I sat down on the couch because my legs wouldn't hold me anymore. Paul sat beside me, close enough that I could feel his warmth. Elaine stood there like she was waiting for permission to exist. I opened the envelope carefully, afraid it might disintegrate in my hands. Inside was a single sheet of paper, the handwriting wandering across the lines like Mom had been trying to write in a moving car. 'My dear girls,' it started, and I had to stop because I couldn't see through the tears. I wiped my eyes and kept reading. 'I'm writing this on a good day. I don't have many of those anymore. I know something is wrong with me. I've known for a long time, even when everyone kept saying I was fine, that it was just stress, just age, just normal forgetfulness. But I know my own mind, and I know when it's betraying me.' My chest felt like it was being crushed. She went on. 'The worst part isn't the forgetting. It's the fear. I'm afraid all the time now because I can feel myself slipping away and no one will acknowledge it. They smile and nod and tell me I'm doing great, and I want to scream at them that I'm not, that something is terribly wrong.' She wrote, 'They tell me I'm fine, but I know I'm not. I know something is wrong, and I'm afraid they'll stop listening.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Hospital Papers

I turned the page over, my hands shaking so badly the paper rattled. Mom's handwriting got smaller here, tighter, like she was running out of space or running out of courage. 'Your father means well, I think. But he doesn't want to see it. And there are others who definitely don't want to see it because if they admit I'm sick, they might have to change how they're doing things. A nurse came by last week with papers. She was so friendly, so professional. She said they were just routine hospital documents, forms everyone has to sign. Your father was there, and he kept nodding, encouraging me to sign. I tried to read them but the words kept sliding around on the page. I asked what they were for and the nurse just kept smiling and saying, don't worry, it's all standard procedure. So I signed them. I signed papers I didn't understand because everyone was telling me it was fine.' I felt Paul's hand grip mine tighter. Mom's writing got even shakier. 'I've thought about those papers every day since. I don't know what I signed. I don't know what I agreed to. And I'm terrified that I gave away something important, something I should have protected.' The words were almost illegible now. 'Your father brought papers,' she wrote. 'The nurse said they were for the hospital. But I don't remember what I signed.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Warning

The final paragraph was on the back of the page, written in even shakier letters that broke my heart. 'If you're reading this, I'm probably gone or I'm so far gone I don't remember writing it. I'm hiding this in my recipe book because I know one of you girls will find it eventually when you're going through my things. I need you to know that I tried. I tried to speak up, to make them listen, to get help before it was too late. But I wasn't loud enough or strong enough or believed enough. And now it's too late for me.' She wrote more, and this part made me actually gasp out loud. 'One of you might feel this too someday. The doctors say these things can run in families, though they won't say it to my face because they won't admit I actually have anything wrong. If it happens to you—if you start feeling like something's wrong and everyone keeps telling you you're fine—please don't do what I did. Don't be quiet. Don't be polite. Don't let them make you doubt yourself until it's too late to fight back.' The final lines were almost illegible. 'One of you might feel this too,' Mom wrote. 'Don't let them tell you it's nothing. Trust yourself. I should have.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Reckoning

I looked up from the letter to find Elaine watching me with an expression of absolute terror. Paul's arm was around my shoulders, and I could feel him breathing, steady and solid, the only thing keeping me grounded. 'She knew,' I said, my voice coming out strangled. 'She knew exactly what was happening to her, and she knew it might happen to one of us, and you kept this from me.' 'I thought I was sparing you,' Elaine said, but her voice had no conviction left in it. 'Sparing me?' I stood up, the letter still clutched in my hand. 'I've spent years thinking I was crazy. Years fighting to get doctors to take me seriously, wondering if I was imagining things, doubting every symptom because everyone kept telling me I was fine. And the whole time, you had proof that Mom went through the exact same thing. You had her voice telling us not to make the mistakes she made, and you kept it locked away.' Elaine was crying again, but I felt nothing for her tears now. 'She wrote us a map,' I said, holding up the letter. 'She left us instructions on how to fight back, how not to be silenced the way she was, and you buried it because you couldn't handle the truth about Dad.' 'You kept her voice from me,' I said, and Elaine crumpled onto the couch, sobbing like a child.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Breaking Point

We sat there for what felt like hours, the three of us in that living room that suddenly felt like a stranger's house. Paul eventually went to make tea, and I could hear him in the kitchen, the familiar sounds of cups and spoons, the kettle heating. Elaine had stopped sobbing, but she looked hollowed out, her face blotchy and swollen. I kept looking at Mom's letter on the coffee table between us, her handwriting like a ghost reaching across decades. 'I was twenty-three when she died,' Elaine said finally, her voice raw. 'I was pregnant with Jessica, and I couldn't face the idea that I might have inherited it. That my daughter might. So I convinced myself it wasn't genetic, that the doctors were wrong, that if I just never thought about it again, it wouldn't be real.' I understood the impulse—God knows I'd spent years trying to convince myself my symptoms were nothing. But understanding didn't equal forgiveness. 'You had a choice,' I said quietly. 'You could have warned me. You could have given me her words.' 'I know,' she whispered. 'I know, and I was wrong. I was so wrong.' Paul brought the tea, and we sat there drinking it in silence, mourning the years we'd lost to her secret. I didn't know if our relationship could survive this betrayal, if the trust could ever be rebuilt. But when Elaine reached for my hand across the coffee table, I didn't pull away. 'I'm sorry,' she whispered, and I didn't know if I could ever forgive her—but I knew we had to try.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Next Morning

I woke the next morning with Mom's letter on my nightstand, where I'd placed it before falling into an exhausted, dreamless sleep. Paul was already up, and I could smell coffee brewing downstairs. For the first time in months—maybe years—I felt something shift inside me. Not relief exactly, but clarity. A sense of direction. I finally had proof that I wasn't crazy, that my symptoms were real and inherited and documented. I had my mother's voice telling me to fight back, to not let doctors dismiss me the way they'd dismissed her. I got out of bed and went to my desk, pulling out the folder where I'd kept all my medical records, all the notes from appointments where doctors had suggested therapy or hormones or stress management. I added Mom's letter to the pile, along with the death certificate Elaine had finally given me. This was my ammunition now. This was the evidence that would make them listen. Paul found me there an hour later, still in my pajamas, organizing everything into a timeline. 'You're really doing this,' he said, and it wasn't a question. 'I'm really doing this,' I confirmed. 'Dr. Whitmore said she'd refer me to specialists if we found any family history. Well, now we have it.' I called Dr. Whitmore's office and scheduled a follow-up, this time with Elaine's medical history in hand.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

The Family Meeting

Two days later, Elaine and I sat across from Jessica in her apartment, a small but bright space in the city where she worked as a graphic designer. She'd sensed something was wrong the moment we arrived together—we never visited together anymore, hadn't in years. 'What's going on?' she asked, looking between us with growing alarm. I let Elaine start. She owed her daughter that much, to be the one to explain what she'd hidden. Elaine told her about our mother's illness, about the early-onset dementia that had been dismissed as hysteria, about the genetic component the doctors had suspected but never confirmed. She told her about the letter, about keeping it secret all these years. I watched Jessica's face go through the same stages I'd experienced—confusion, disbelief, anger, fear. 'You're telling me I might have inherited a genetic brain disease, and you never thought to mention this?' Jessica said, her voice tight. 'You let me go through genetic counseling before I had kids without ever mentioning our family history?' Elaine was crying again, but Jessica wasn't interested in her mother's tears. She turned to me instead. 'What are you doing about it? About your symptoms?' I told her about Dr. Whitmore, about the referrals I was pursuing, about the genetic testing that might finally give us answers. Jessica listened, her face going pale, and then she said, 'I want to be tested. Right away.'

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI

Reclamation

That night, back home with Paul, I read Mom's letter again. I'd probably read it fifty times by now, but each time I found something new in her words—some turn of phrase that reminded me she'd been real, she'd been fighting, she'd been trying to leave us something more than silence. 'Do you think she knew how much this would matter?' Paul asked, sitting beside me on the couch. 'I think she hoped,' I said. 'I think she was terrified we wouldn't find it in time, but she hoped.' I thought about all the years I'd spent doubting myself, all the doctors who'd dismissed me, all the times I'd wondered if I was imagining my symptoms or exaggerating or just being difficult. And I thought about Mom, who'd gone through all of that and worse, who'd been silenced and medicated and locked away, who'd died without anyone believing her. She hadn't had the words to fight back, or maybe she'd had them but no one would listen. But I had her words now. I had her story. And I had my own voice, stronger for knowing hers. The genetic testing might show I inherited her condition, or it might not. The specialists might find answers, or they might not. But I had already found something more important than a diagnosis. I didn't have a cure, but I had something better: the truth, my voice, and the resolve to make sure no woman in our family would ever be silenced again.

Image by RM AI

Image by RM AI